Today is Memorial Day, the day Americans pause to remember those who gave their lives in service to their country. Today I would like to remember my Dad, William Stewart Leslie (1923-2005). He did not fall in combat, but he served honorably in World War II and the Korean Conflict. He loved his country and taught me to do the same. He fought the real battle to provide for his wife and six kids, all of whom grew up to become decent, honorable, compassionate men and women because of lessons he taught us. He passed from this life in February 2005 after a long battle with lung cancer.

In World War II he served with the U. S. Ninth Air Force based in England. For the most part, he flew P-51 fighter planes. One of his assignments was to shoot down German V-1 and V-2 rockets launched from Holland. He said the rockets were so slow and crude that often just the "prop wash" or air turbulence from his plane flying past the rocket was enough to send it crashing harmlessly into the sea. He told us stories of the funny things that happened during his wartime service: the time he got his cap blown off because he unwittingly stood in front of a loaded cannon, or the time he was appointed "mess officer" for his unit despite the fact that he had no idea how to run a mess hall. He never talked about the scary things, of which I'm sure there must have been a few. I believe he was shot down once. He didn't like to talk about it. Towards the end of his life he had nightmares from which he woke up screaming. I couldn't help wondering if those came from long-buried frightening moments from his war years.

I asked him once if there was ever a moment when he was afraid for his life, scared that he might die. No, he replied, because when you're 19 years old, you're too dumb to be scared. You are convinced that you're 20 feet tall and bulletproof. The other guy will get shot, not you. When I saw TV news stories about the dedication of the World War II Veterans Memorial, I was overcome with a wave of pride and affection for him and called to tell him so. His response, like so many others of "The Greatest Generation" was typical.

"Shoot," he said, "I didn't really do anything."

Yes, you did. And we are grateful.

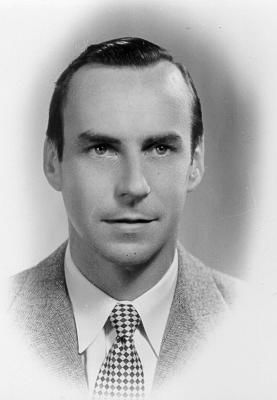

During the Korean Conflict he was recalled to active duty from the reserves. Somewhere along the way he mentioned his desire to learn Russian, and the next thing he knew, he was enrolled in a special program in Washington, D. C. to study Russian language, history, culture, and geopolitics. It wasn't top secret, but it was confidential. He was instructed to wear civilian clothes and, if asked, just say that he worked for the Defense Department and leave it at that. I believe the photo you see might come from this period. You'll notice that he's standing or sitting against a neutral background, he's well dressed, and looking directly at the camera with a serious expression. It looks like an ID or passport photo to me, but I can't be sure.

Many of his professors in this special program were White Russians or anti-communists who fled after the revolution of 1917. He was amazed at what they knew and how they knew it. Once, after class, one of his professors approached him furtively, looking both ways before speaking.

"Gaspadin (Mister) Leslie," the man said in Russian, "You are . . . pilot, da?"

"Da," Dad replied. He hadn't told anyone he was a pilot.

"I teach you Russian. You teach me to fly, da?"

"Da."

Dad went to a local airport, rented a small plane, and took his professor up for a flying lesson, but quickly realized he didn't have the specialized vocabulary needed to explain the more technical aspects of flying: artificial horizons, ailerons, rudders, pitch, and yaw, and so forth. His efforts to teach his teacher how to fly ended right there, but I've always thought it was a great story. There was also the time a friend of his passed himself off as a native Russian to impress a bimbo and Dad played along; or the time a drunk driver rammed into the picture window of the trailer Dad had rented while he, Mom, and my sister Susan (an infant at the time) were driving cross country. Dad was full of stories, and he told some of them so many times, we were sick of them. Now that he's gone, I'd give anything to hear him tell them again.

He was not a perfect man (no one is), but he was a good man. I think, like many men who came of age during the Great Depression and World War II, he found it difficult to express his deepest emotions in public. Bragging, being conceited, or having an overly exalted opinion of oneself was the worst sin a man could commit. You were supposed to work hard, do your duty, and not call attention to yourself. People made fun of Bob Dole, also a World War II veteran, for sometimes speaking of himself in the third person ("Bob Dole knows . . .") but I believe the habit came out of that fundamental modesty of his generation. Nowadays, when celebs and ordinary people get on TV talk shows, air their dirty laundry in public, and then get all weepy while the rest of us watch, such circumspection and humility are refreshing.

Sometimes, however, I think Dad went too far in trying to prevent us from becoming conceited. His favorite tactic was to conceal his real feelings behind a joke or a left-handed compliment. It made me think sometimes that nothing I did mattered to him. In college I was nearly a straight A student, but in college I also acquired my first serious girlfriend, and I loved her with a passion that only those in love for the first time can manage. I was worried that my grades were slipping because we were spending so much time together. I needn't have worried. Dad's response? "He had a 4.0, but then he met this girl. Ha, ha, ha." It made my blood boil.

I once asked him angrily why he seemed so allergic to paying me a compliment in public. "Because I don't want you to get the big head," he snapped back. We had some friction over the years, to say the least. If there was any good thing about his long final illness, it was that we each had time to look past the bluster and bravado and hurt feelings and say to each other, "I love you and I am proud of you."

I know that he loved me despite the fact that he sometimes had trouble expressing it. He had many jobs throughout his life, and some were more successful than others: airline pilot, filmmaker, salesman, retail business owner. For most of the time I was growing up, he was the regional sales representative for a company that sold heavy construction equipment. His territory extended from Maryland to Mississippi, and often he would leave on business trips on Monday morning and not return until Friday night. That had to be hard, lonely work, but he did it because he loved us. He never once failed to provide us with anything we needed (and often just things we wanted) even if it meant considerable personal and financial sacrifice for him. My three-week trip to England when I was in college that he paid for is a prime example. Now that I'm living on my own and struggling to pay bills just for myself, I have a glimpse of what he must have struggled with to support and provide for a wife and six children.

He stayed with me faithfully whenever I had to be hospitalized for surgery related to my disability. Once in particular, I went through a kind of withdrawal as I came down off the painkillers and anesthesia. I was terrified, convinced that something awful was about to happen, and didn't want to be left alone. He stayed with me, after visiting hours were over, until I fell asleep. I awoke hours later in complete peace and darkness as all the chemicals had left my body. I called out to him but realized he must have slipped out after I fell asleep. I was so grateful to him! Last year, after his passing, when I was in ICU with that terrible bladder infection, I thought that if I squinted hard enough I could almost see him sitting in the chair at the foot of the bed as he had so faithfully so many times before.

There's a sequence from the movie It's a Wonderful Life that expresses perfectly how I feel about my Dad. Young George Bailey is working for Mr. Gower, the local druggist, as a delivery boy. One day, George notices that Mr. Gower has received a telegram informing him that his son has died of influenza. Mr. Gower, distraught with grief, has accidentally put rat poison into some capsules, and sent George out to deliver them, thinking they are medicine for a sick little boy. George, knowing the truth, looks around desperately for help. Suddenly, he sees a billboard reading, "Ask Dad. He knows." George runs off, tries to tell his father what's happened, and waits for Mr. Gower to come to his senses. When George tells Mr. Gower what's happened, the man is incredibly grateful. George's quick thinking has saved a boy's life and Mr. Gower's business.

Dad was always that anchor of stability and wisdom for me in the same way that George Bailey's dad was for him. Even when we were bickering, I knew that if I really got in a jam, I could ask Dad. He knew. He would fix it. He would make it OK. Because he was Dad. I miss him. But I remember what he taught me about hard work and doing your best and keeping your promises. And I know. And it will be OK.

Eternal Rest grant unto him, O Lord, and may perpetual light shine upon him. Amen.

Rest in peace, Dad. I love you.

No comments:

Post a Comment